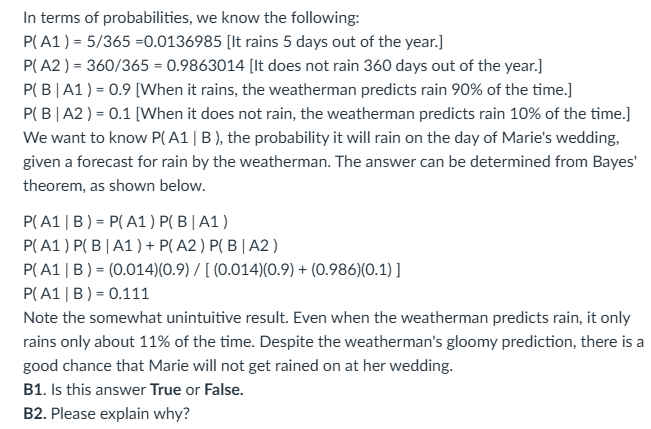

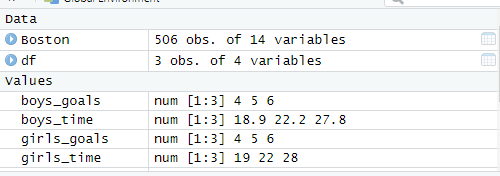

For my final project, I sought a dataset related to housing, as I work in property management and felt housing was a good starting point. I settled in using a dataset bult in R, the ‘Boston’ dataset. This dataset has 506 observations and 14 variables:

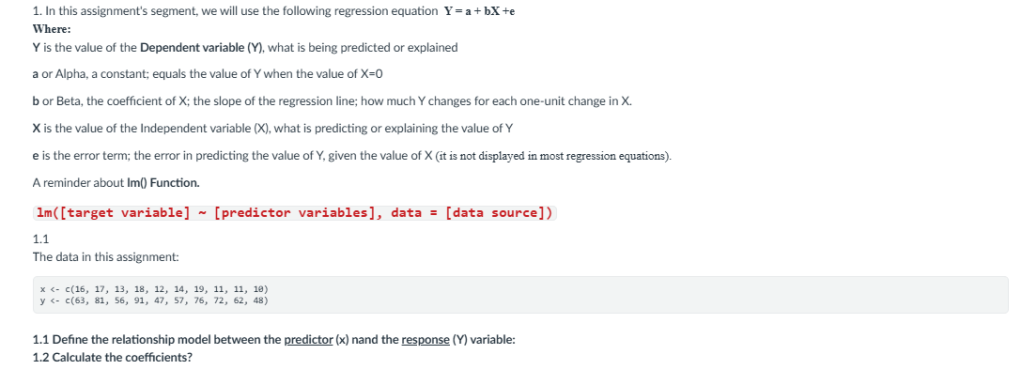

Hypothesis using the Boston dataset:

Do homes near the Charles River (chas=1) have higher median home values than homes not near the river?

Homes near the river do not have higher median value than those not near it.

Homes near the river have higher median value.

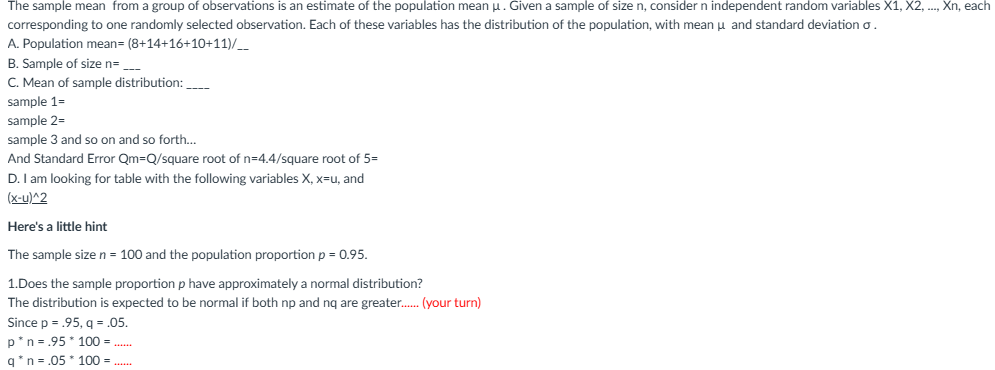

Sample:

For this project, I am asked to take a sample in order to establish my hypothesis:

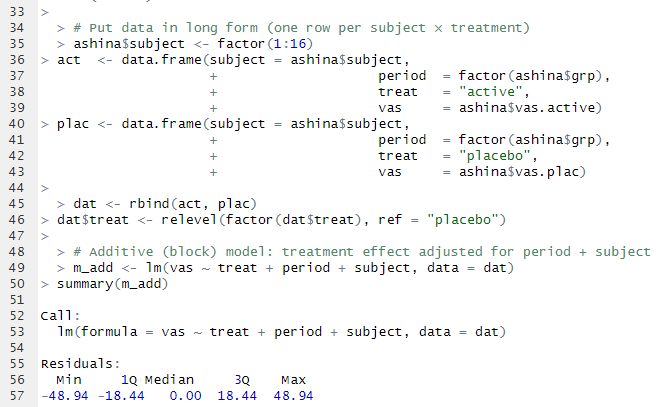

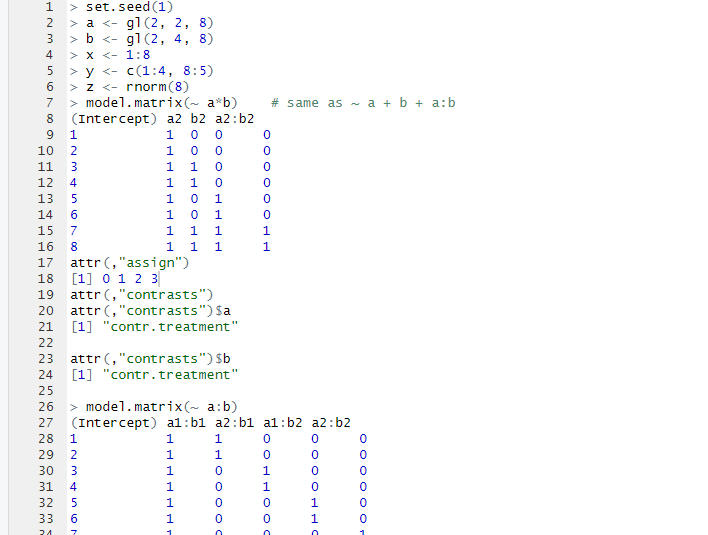

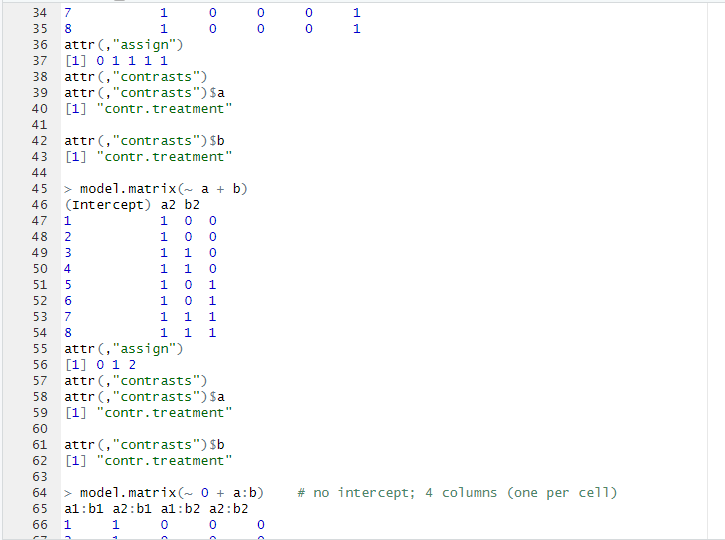

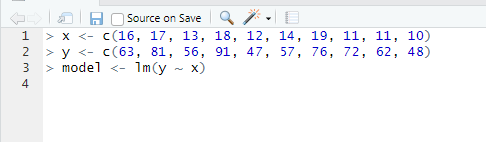

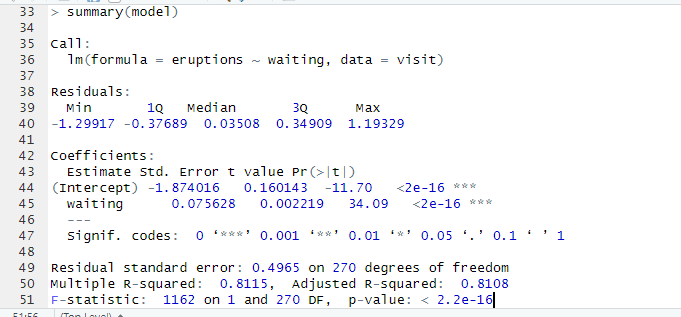

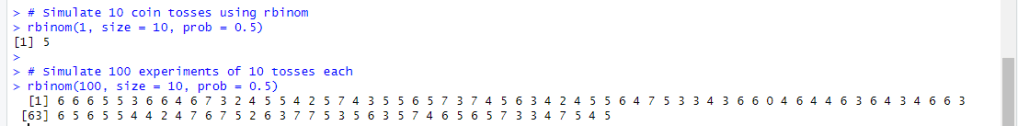

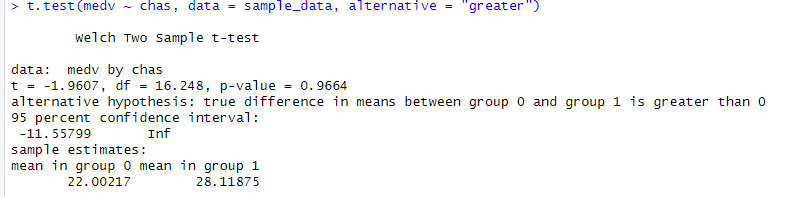

Running a T-Test in R:

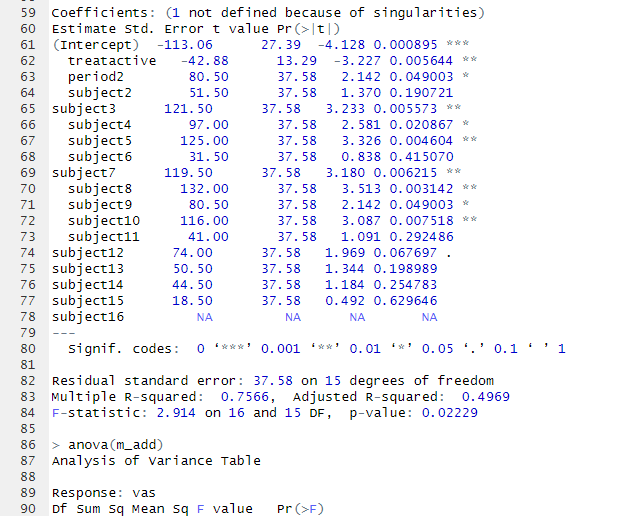

Interpreting the Results:

- t = –1.9607

- df = 16.248

- p-value = 0.9664

- Mean (not near river, chas=0) = 22.00

- Mean (near river, chas=1) = 28.12

In this case, we Fail to reject the null hypothesis (H₀).

There is no statistical evidence that homes near the river (chas = 1) have higher median values than homes not near the river in this sample.

Even though the sample means suggest river homes are more expensive (28.12 vs 22.00), the difference is not statistically significant.

A Welch two-sample t-test was conducted to determine whether homes located near the Charles River (chas = 1) had higher median home values (medv) than homes not located near the river (chas = 0). The analysis used a random sample of 200 observations from the Boston Housing dataset.

The mean home value for properties not near the river was 22.00 (in units of $1,000), while the mean for homes near the river was 28.12. Despite the difference in sample means, the one-sided t-test indicated that this difference was not statistically significant (t = –1.96, df = 16.25, p = 0.9664). The 95% confidence interval ranged from –11.56 to ∞, which includes zero and suggests that the true difference could be negative, zero, or positive.

Based on these results, there is no evidence to conclude that homes near the Charles River have higher median home values than homes not near the river.

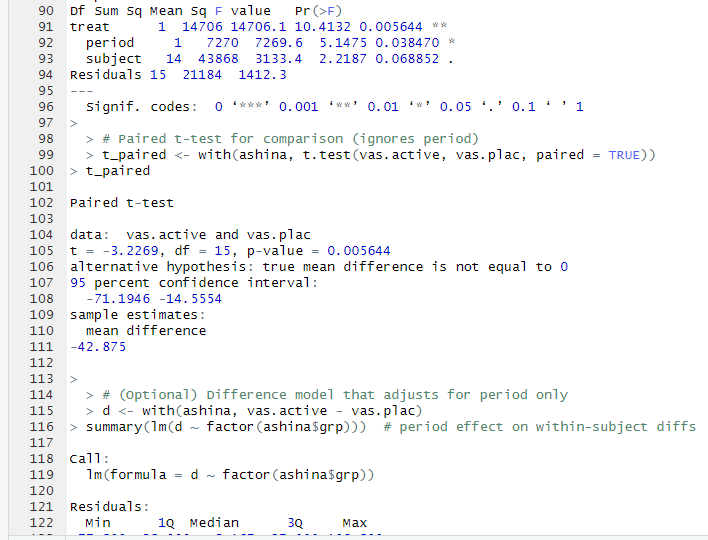

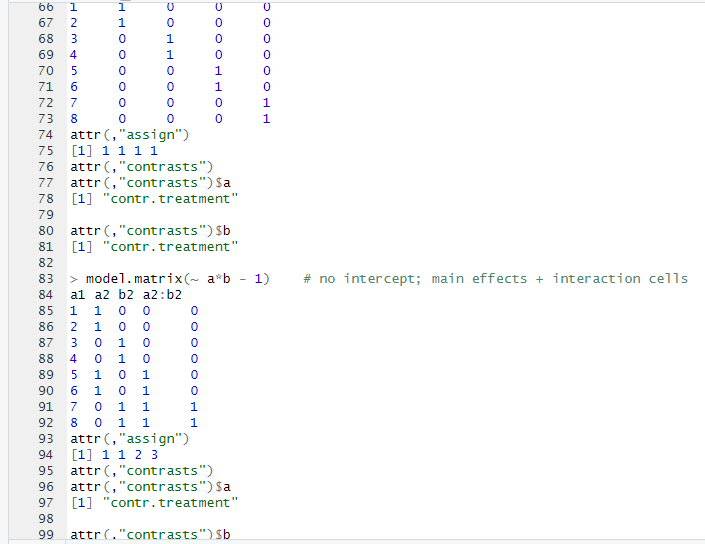

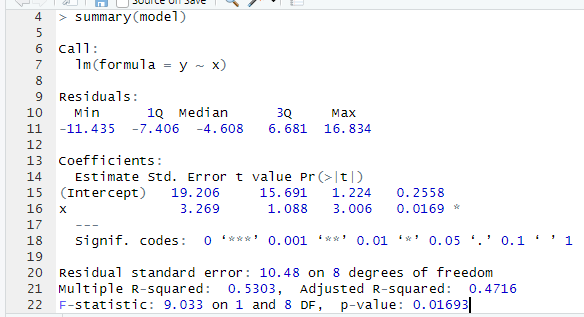

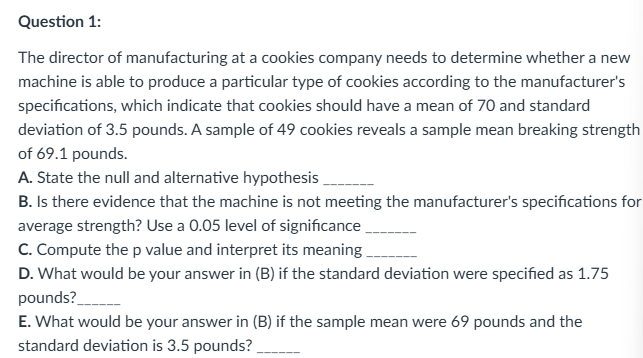

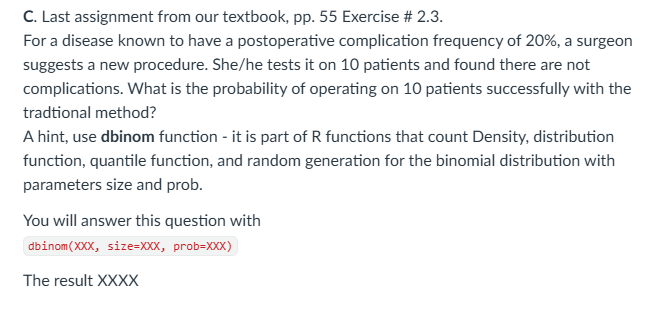

Creating a Visualization in R:

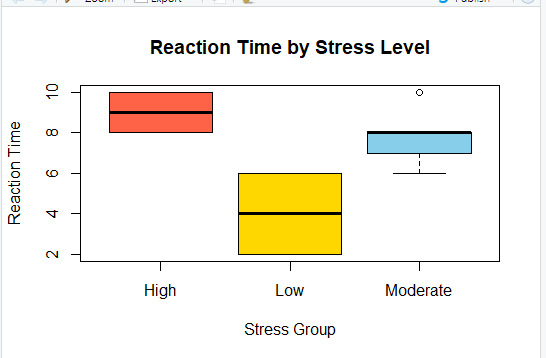

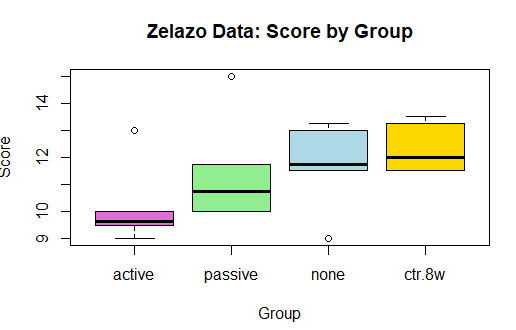

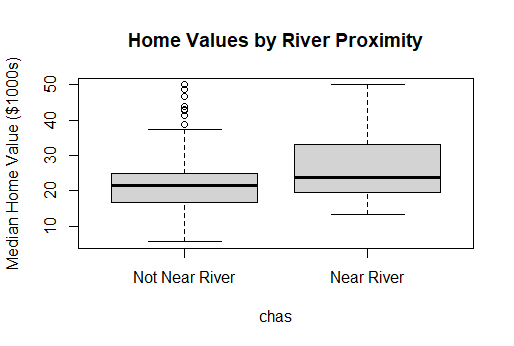

Interpretation of Box Plot:

The boxplot comparing median home values for river-adjacent homes (chas = 1) and non-river homes (chas = 0) shows that homes near the Charles River tend to have a higher distribution of median values. The median for river homes appears higher, and the overall spread of values is shifted upward relative to homes not near the river.

However, despite the visual difference in the boxplot, the statistical test did not find this difference to be significant. The t-test produced a p-value of 0.9664, which indicates that the observed difference in medians is likely due to random sampling variability rather than a meaningful effect of river proximity.

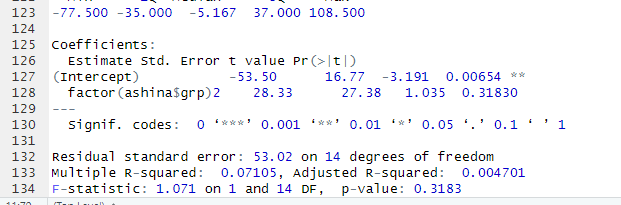

Write Up/Abstract:

This project examines whether proximity to the Charles River is associated with higher residential property values in the Boston area. This question fits directly into the inferential methods covered in class, where we learned to compare group means using tools such as t-tests, confidence intervals, and hypothesis testing. Using a random sample of 200 observations from the Boston Housing dataset, a two-sample Welch t-test was conducted to compare the median home values of tracts bordering the river (chas = 1) and those not bordering it (chas = 0). This method was chosen because it does not assume equal variances between the groups. The sample mean value for river-adjacent homes was 28.12, compared to 22.00 for non-river homes. However, the difference was not statistically significant (t = –1.9607, df = 16.248, p = 0.9664). The 95% confidence interval for the difference in means ranged from –11.56 to infinity, indicating that the true difference may be zero or even negative. These findings provide no evidence that homes near the Charles River have higher median values, suggesting that river proximity does not significantly influence property value in this dataset.